Breaking Update: Here’s a clear explanation of the latest developments related to Breaking News:World’s longest-running lab experiment: Running for 100 years, still ‘no live witness’ |– What Just Happened and why it matters right now.

Ever wonder what true patience looks like?Today, we are running behind instant results and getting everything we need right at our fingertips, with just one click.On the contrary, one experiment completely changes our views and teaches us that real discoveries sometimes demand waiting – for years, even decades, for nature to reveal its secrets.A nearly century-old setup shows just the correct reflection of life: solid on the surface, fluid underneath, with drops of wisdom falling when least expected.

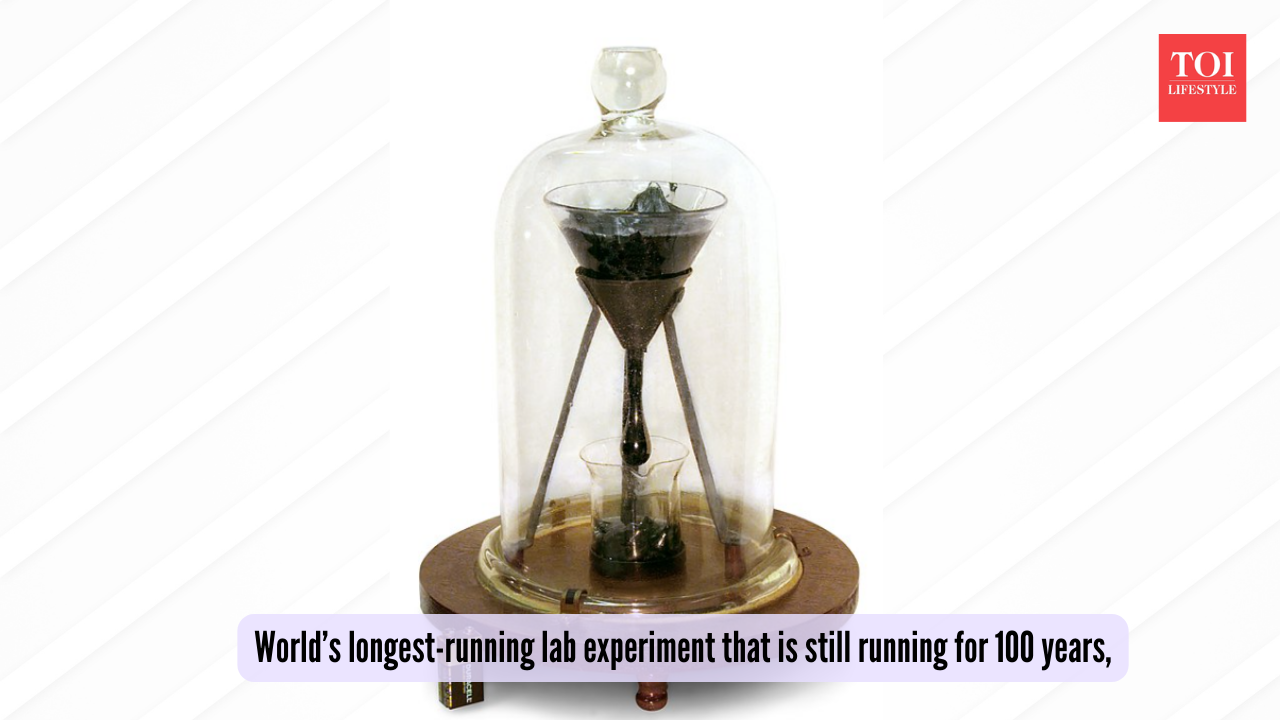

World’s longest-running lab experiment that is still running for 100 years (Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

An experiment that lasted for over 100 years

Back in 1927, University of Queensland physicist Thomas Parnell wanted to prove pitch, a tar derivative that looks rock-solid, is actually a super-viscous fluid, 100 billion times thicker than water. He heated the pitch, poured it into a sealed glass funnel, let it settle for three years, then cut the stem in 1930 to start the flow. Parnell wanted to show students how everyday things hide surprises, as detailed on the University of Queensland’s official Pitch Drop page.

Drops that take forever

The first drop didn’t fall until December 1938, over eight years later. Since then, only nine have dripped out, roughly every eight to ten years. Air conditioning in the 1980s even slowed it down. The ninth hit in April 2014, and scientists expect the tenth sometime this decade. No one has ever caught a drop live, despite cameras and a live stream, as glitches always intervene, per Guinness World Records.

Scientists who never saw the magic

Parnell oversaw it until the 1960s, followed by John Mainstone from 1961 to 2013. Mainstone watched for 52 years but missed drops due to mishaps, like a 2000 thunderstorm killing the feed and stepping out during the 1988 Expo fall. Both died without witnessing one. Current custodian, physics professor Andrew White, keeps vigilant care of the experiment, calling it history’s most famous patience test, according to Wikipedia’s detailed timeline.

Kevin’s Glacier Model

Why it still drips on

Held in a glass dome outside a lecture theatre, the setup proves pitch flows like a fluid despite its solid-like look, which was once used to seal ships. Guinness lists it as the longest-running lab experiment, with enough pitch for another century. Parnell won an Ig Nobel posthumously in 2005 for it, shared with Mainstone, as written in historical accounts. Tech glitches, like power failures, have thwarted watches, but the live stream at thetenthwatch.com still carries on.

Lessons from a century of waiting

This demo of viscosity looks interesting because it’s raw science – slow, unglamorous, and profound. “The experiment was started in 1927 by Thomas Parnell… to demonstrate to students that some substances which appear solid are highly viscous fluids,” explains Wikipedia. At 96 years strong, it reminds us discovery isn’t always massive; sometimes it’s about patience and the wait for that one, elusive drop.Photos: Wikimedia Commons