Breaking Update: Here’s a clear explanation of the latest developments related to Breaking News:The fru gene specifies male cooperative behaviors in honeybee colonies– What Just Happened and why it matters right now.

The male-specific FruM protein is highly spatially and temporally restricted in the nervous system

Our detailed nucleotide sequence transcript analyses revealed that the fru gene in honeybees is transcribed from at least three promoters based on three different transcription start sites. The three transcripts that derive from promoters P1 to P3 encode protein variants with a common Broad-Complex, tramtrack and Bric-à-brac (BTB) domain and three alternative zinc finger (ZnF) domains that are produced via alternative splicing and inclusion of either exons 9A, 9B and 9C (Fig. 1b–d; EMBL-EBI accession number: OZ362630-OZ362641). Only the P1-derived fru transcripts (fruP1) are sex-specifically spliced. In males, the skipping of exon 3 results in male-specific fruP1 transcripts (fruM), which encode 386– to 459-amino-acid-long protein isoforms with three alternative ZnF domains, suggesting that this is a male-specific BTB ZnF transcript, fruM (Fig. 1c). In females, exon 3 is retained, which results in an early translation stop codon of female-specific fruP1 transcripts (fruF) and a predicted 34-amino-acid-long protein that lacks the BTB and ZnF domains (Fig. 1c). To determine whether sex-specific fruP1 transcripts are controlled by the sex determination cascade, we performed RNAi-induced knockdown of the fem gene, a key sex determination regulator31 (Fig. 1a). The fem RNAi-treated females produced male-specific fruP1 transcripts but also female-specific transcripts at larval stage 4 (Fig. 1e and Supplementary Table 2) suggesting a partial shift toward male splicing in response to temporally restricted fem knockdown, which we induced in the embryo31. This result suggests that this male-specific splice regulation requires the absence of female-determining activity from the fem gene, a component of the canonical sex determination pathway30,31,36.

In newly eclosed adult males, sizeable amounts of fruM transcripts are found in the brain and ganglia but not in other tissues, including the thorax muscle, fat body, or gonads (Fig. 1f). This finding suggests a spatial restriction of fruM transcripts to the nervous system. During development, sizeable quantity of fruM transcripts are found from early pupation stages on in the head (Fig. 1g). This finding indicates that expression starts in the nervous system at early pupation, when the adult nervous system is formed37. Next, we developed an antibody against a sequence of the BTB domain. Using confocal light microscopy sections, we found that the anti-Fru antibody labels male but not female pupal brains in spatially characteristic patterns (Fig. 2a, b and Supplementary Movies 1 and 2), suggesting that these male-specific labels derived from P1, but not P2 or P2 transcripts. To examine whether this male-specific expression pattern was specifically derived from FruM protein expression, we generated fruP1− mutants. We deleted the P1 promoter and exons 1 and 2 sequences using the CRISPR/Cas9 method in embryos29,32,38 (Fig. 2c), reared homozygous queens carrying this deletion, and confirmed the fruP1-/- genotype at the nucleotide sequence level (Supplementary Fig. S1). These queens produced haploid unfertilized eggs from which our fruP1− male progeny were derived. The fruP1− males lacked the fruM transcript (Supplementary Fig. S2) and did not present consistent male-specific Fru protein labels as observed in staining of the wt males (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Movie 3). These results suggest that the male-specific FruM protein is expressed from the male fruM transcripts, that the anti-Fru antibody labels Fru protein expression, and that the fruP1− mutant is a loss-of-function mutation of fruM.

a Anti-Fru immunostaining of midbrains of wt males, wt female workers and fruP1− pupae (P5 stage). Cyan: anti-Fru staining. Magenta: phalloidin counterstaining. n = 7 bees were examined. Scale: 100 μm. b Scheme of the anatomy of the bee brain. MB, mushroom body. LO, lobula. LH, lateral horn. PE, peduncle. CX, central complex. AL, antennal lobe. SEZ, subesophageal zone. This graphic was created using BioRender. c Deletion of the P1 promoter and exon 1 and 2 genomic sequence generated fruP1−males. The boxes represent exons. Blue: male specific. Red: female specific. Arrowheads: target sites of sgRNAs 6 and 12. d Number of FruM-expressing cells in the adult male midbrain. Twelve brains were examined. Medians (middle line) and quartiles are shown.

We found that our anti-Fru labels colocalized with nuclei (Supplementary Fig. S3). These labels were mostly organized in characteristic clusters, which were frequently located in the outer anterior and posterior sections of the male brain (Fig. 2a, b). We also detected such sparse Fru protein labels in the ganglia (Supplementary Fig. S4), suggesting that FruM expression expands to the ventral nerve cord. To determine how many cells express the FruM protein, we counted Fru-labeled nuclei in the adult male midbrain (which consists of approximately 400,000 neurons16) and found that approximately 1800 cells expressed FruM proteins (Fig. 2d). Collectively, these results suggest that the male-specific transcription factor protein FruM is highly spatially and temporally regulated in the developing and adult male nervous systems.

FruM-expressing cells are involved in processing and integrating information from different sensory modalities

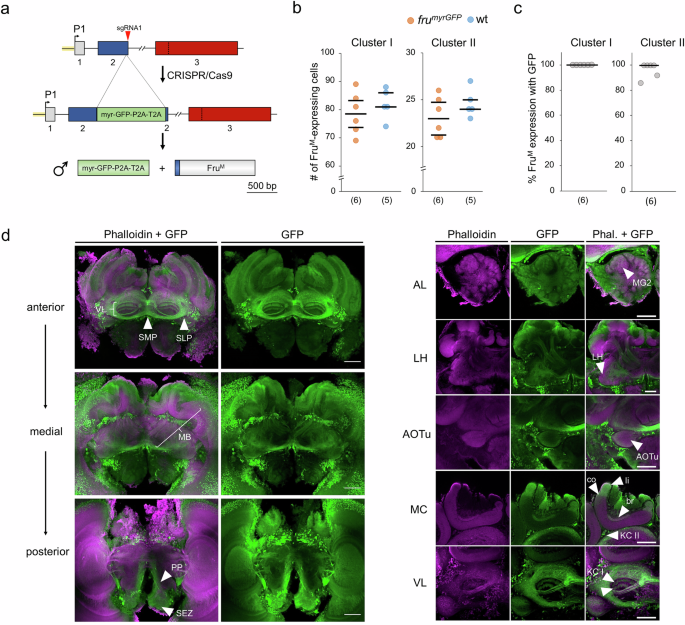

As it is unclear where FruM is expressed in the male brain, we inserted the myrGFP/P2A/T2A coding sequence into the fru locus using the CRISPR/Cas9 method29,38,39 so that the fruP1 transcripts expressed both membrane-tethered GFP (myrGFP) and FruM proteins (Fig. 3a, Supplementary Fig. S5). We examined two neural clusters to determine whether the insertions generated robust labeling of Fru-expressing cells. The number of Fru-expressing cells in the frumyrGFP males did not differ from that in the wt males as revealed from anti-Fru antibody staining, suggesting that this genomic insertion did not disrupt the formation of these neurons (Fig. 3b and Supplementary Fig. S6; Cluster I (P = 0.54), Cluster II (P = 0.33), MWU test). On average, 100% and 96% of the anti-Fru-labeled cells in the two clusters were also positive for GFP, suggesting robust GFP labeling of the Fru-expressing (FruM+) cells (Fig. 3C and Supplementary Table S3).

a Insertion of a myrGFP coding sequence into the fru genomic locus. P1: promoter 1. Green box: donor sequence encoding the membrane-tethered myrGFP protein and the P2A/T2A peptides mediating the two proteins. b FruM-expressing (FruM+) neuronal somata in Cluster I (approximately 78 cells) and Cluster II (approximately 23 cells) of frumyrGFP and wt males. Cluster I (P = 0.54, z = 0.74); Cluster II (P = 0.33, z = 1.0), MWU test. c Proportion of FruM cells expressing myrGFPs in the somata of the two clusters. All statistical tests were two-sided. (n) below graphs (b) and (c): the number of bees examined. d Confocal images of the frumyrGFP male brain. Labeling of F-actin (via phalloidin, magenta) and FruM (via anti-GFP, green) proteins. n = 8 bees were examined. Left panel: Anterior, medial and posterior overviews of the FruM+ circuitry in the midbrain. Anterior: FruM+ axons in the vertical lobe (VL), superior medial protocerebrum (SMP, arrow), and superior lateral protocerebrum (SLP, arrow). Medial: FruM expression in the peduncle and calyces of the mushroom body (MB). Posterior: Neuronal cells in the periesophageal neuropil (PP, arrow) and subesophageal zone (SEZ, arrow) showing FruM expression. Right panel: Details of the FruM+ circuitry. AL: antennal lobe. FruM+ in macroglomerulus 2 (MG2; arrowhead). LH: lateral horn. FruM+ in the lateral horn (arrowhead). AOTu: anterior optical tubercle. FruM+ cells of the optical tubercle (arrowhead). MC: medial calyx. FruM+ in the basal ring (br, arrowhead), collar (co, arrowhead), lip (li, arrowhead), and FruM+ somata of type II Kenyon cells (KC II, arrowhead). VL: vertical lobe. FruM+ type II Kenyon cells in the strata of the vertical lobe that project from the lip (arrowhead) and outer collar zones (arrowhead below). Scale 100 μm.

We detected a number of FruM+ cell populations in brain areas with known functions14,40,41 (Fig. 3d and Supplementary Movies 4–7). We observed FruM+ neurons in periesophageal neuropils (PPs) in the posterior region (Fig. 3d), which are involved in processing mechanosensory and gustatory information. One tract runs medially on each side of the brain, possibly connecting with the superior medial protocerebrum (SMP, Fig. 3d). In the antennal nerve, we identified FruM+ neurons (antennal tracts T5 & T6, Supplementary Movies 4 and 5) that project into the antennal mechanosensory and motor center (AMMC; Supplementary Movies 4 and 5) and possibly into the subesophageal zone (SEZ; Fig. 3d), indicating that mechanosensory and/or gustatory neurons are involved. The olfactory sensory neurons (OSNs) entering the antennal lobe (AL) were not stained (Supplementary Movies 4 and 5). Many glomeruli in the AL (the primary olfactory processing center) exhibit FruM+ in their core region. This includes the male-specific macroglomeruli MG1 and MG2 (AL, Fig. 3d), the latter of which processes the sensory input from the queen pheromone 9-ODA18. The glomerulus core FruM+ circuitry primarily contains processes from local neurons (LNs), because projection neurons (PNs) extending to the mushroom bodies (MBs) were not labeled (Supplementary Movies 4 and 4). The lateral horn, another center of the olfactory pathway, shows some FruM+ fibers (LH, Fig. 3d). Several FruM+ neurons in the middle brain belong to output tracts of the visual system. The anterior optic tract (AOT) has some FruM+ cells that project to the anterior optic tubercle (AOTu, Fig. 3d, Supplementary Movies 2–7). Three optic commissures present FruM+ cells that connect the two optic lobes (inferior and posterior optic commissures, IOC and POC) and the two AOTu (vTUTUT: ventral tubercle-tubercle tract; Supplementary Movies 4 to 7). FruM+ neurons are also observed in the optic lobes with diffuse layers in the medulla, clearly stained fibers in the inner chiasma, and three distinct layers in the lobula (possibly corresponding to layers 1, 3, and 5)42 (Supplementary Movie 8 and 9). In the higher-order processing center, the mushroom body (MB), we detected FruM+ neurons in the calyx (see medial calyx (MC), Fig. 3d). FruM+ neurons were found in the lips (li, which receive projections from the antennal lobe43), in the outer collar zone (co, which receives visual input from the lobula and medulla44) and in the basal ring (br, which receives multisensory input from at least the visual and olfactory systems45; Fig. 3d). Intrinsic MB neurons, including a subpopulation of type I Kenyon cells (KCs) and some type II KCs, are Fru positive. The neurites of type I KCs extend along the peduncle and bifurcate into the medial and vertical lobes of the MB, whereas those of type II KCs project only into the most ventral part of the vertical lobe (VL, Fig. 3d). This manifests as different layers in the VL, which include from rostral to caudal, type I KC input from the basal ring (Supplementary Movies 4 and 5), the collar, the lip (VL, Fig. 3d) and type II KC input (Supplementary Movies 4 and 5). FruM+ neurons are also prominently found in anterior parts of the SMP around the medial lobe and in regions corresponding to the superior lateral protocerebrum (SLP, Fig. 3d), including those that connect the two hemispheres41 (Fig. 3d), which possibly represent a hub for preprocessing input from the MB and possibly other regions of the brain. Collectively, these results suggest that the FruM+ circuitry is involved in the processing of sensory information (olfaction, vision, and possibly gustation and mechanosensation) from the periphery to higher-order processing centers such as the mushroom bodies.

FruM+ circuitry has a male-specific anatomy

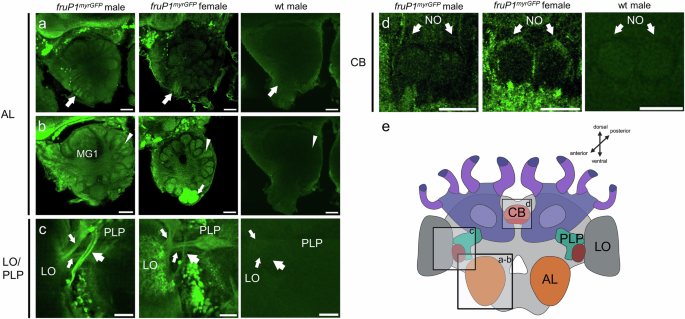

To understand whether the FruM+ circuitry has a male-specific anatomy that can hardwire male-specific behaviors, we generated fruP1myrGFP female workers and compared the labeled structures with those of fruP1myrGFP males. In females, we denote these labeled cells as myrGFPP1+ because the GFP is generated from the same P1 transcript as in males, but these cells donot express the male FruM protein. At the gross level, myrGFPP1+ and FruM+ circuitries in females and males were similar, but neural populations involved in olfactory visual information processing showed notable differences (arrows and arrowheads in Fig. 4 and Supplementary Movies 6, 7, 11 and 13). The antennal nerve is labeled in both male and female worker bees (arrow, Fig. 4a and Supplementary Movie 6, 11 and 13). In workers, a small number (approximately a dozen) of glomeruli on the ventro-medial side of the AL had myrGFPP1+ labels both in the core and cortex (arrow, Fig. 4b), whereas in males FruM+ labels were consistently restricted to the core (arrowhead, Fig. 4b). This female-specific labeling of the cortex suggests that OSNs in the antennal nerve are FruM+ negative in males but some are myrGFPP1+ positive in females. This is supported by a more restricted labeling of the nerve in males than in females (arrows, Fig. 4a: note that the antennal nerve contains approximately 4 times more neurons in males than in female workers14). Hence, sensory neurons from the antennal nerve that bypass the AL and glomeruli on the ventral side (antennal tracts T5 &T6) towards the AMMC and potentially the subesophageal zone (SEZ) were labeled in males but also in female worker bees. The set of worker-specific labeled glomeruli may correspond to the T3b cluster, which may be involved in the processing of cuticular hydrocarbon cues14,46,47. FruM+ circuitry is present in the core of the macroglomeruli, which are male-specific structures not found in workers (MG1, Fig. 4b and Supplementary Movies 6, 11 and 13). The FruM+ circuitry of the male visual system has an extra male-specific tract not found in the myrGFPP1+ circuitry of workers (large arrow, Fig. 4c and Supplementary Movies 7). This male-specific tract projects from the lobula (LO) to the posterior lateral protocerebrum (PLP). However, two other labeled tracts in the same area are shared between males and worker bees (small arrows, Fig. 4c). In the central complex, a few labeled myrGFPP1+ fibers were found in the noduli (NO) of female worker bees, but corresponding FruM+ fibers in males were absent in that region (arrows, Fig. 4d and Supplementary Movies 6, 11 and 13)48. We conclude from these comparisons that the FruM+ circuit has a male-specific identity that manifests at the gross level in the anatomy of the antennal nerve, macroglomeruli, and innervation of the core/cortex of the glomeruli and optic tracts.

a–d Dimorphic fruP1myrGFP-labeled structures and circuitry in male and female worker midbrains. Because FruM proteins are expressed only in males, P1-derived myrGFP expression labels FruM+ cells in males and myrGFPP1+ cells in females. AL antennal lobe, MG macroglomerulus, LO lobula, PLP posterior lateral protocerebrum, CX central complex, NO noduli. Structures were visualized using anti-GFP antibody. Anti-GFP staining of wt males was used as negative control. a The antennal nerve of males and worker females is GFP labeled (arrows). b The male-specific macroglomerulus (MG1) has FruM+ circuitry in the core. Other glomeruli of males and glomeruli of females have labeling of circuitry in the core (arrowheads). Worker bees have a cluster of ventro-medial glomeruli that have myrGFPP1+ circuitry not only in the core but also in the cortex (arrow), a pattern not found in male glomeruli. This female-specific labeling of the cortex suggests that OSNs in the antennal nerve (Fig. 4a) are FruM+ negative in males and myrGFPP1+ positive in females. c A male-specific FruM+ optical tract that connects the LO with the PLP (large arrow). The other two tracts are also labeled in worker bees (small arrows). d A layer of myrGFPP1+ circuitry is found in the NO of female workers. The corresponding FruM+ circuitry is absent in males. e Schematic overview of the honeybee brain and relevant structures. This Graphic was created using BioRender. n = 6 males and n = 7 female bees were examined. Abbreviations as above. Scale 50 µm.

The initiation and sustainment of social feeding behavior dysfunction in fruP1

− males

Sexual maturation of males depends on protein-enriched nutrition which the males receive from the worker bees via trophallaxis behavior. This process requires a sequence of behaviors with the option to quit at a particular step. The male approaches and initiates contact with the worker bee’s head with its antennae while displaying begging behavior. This behavior eventually leads to trophallaxis behavior, in which the male extends its proboscis to the donor worker bee’s mandibles to receive liquid food via mouth-to-mouth transfer10,11. The (nurse) worker bees thereby provide honey liquid from the expandable part of their gut (“honey” stomach), which is enriched with proteins from the hypopharyngeal glands10,12. The components of these proteins are derived from digested and metabolized pollen, which males can hardly digest10,12.

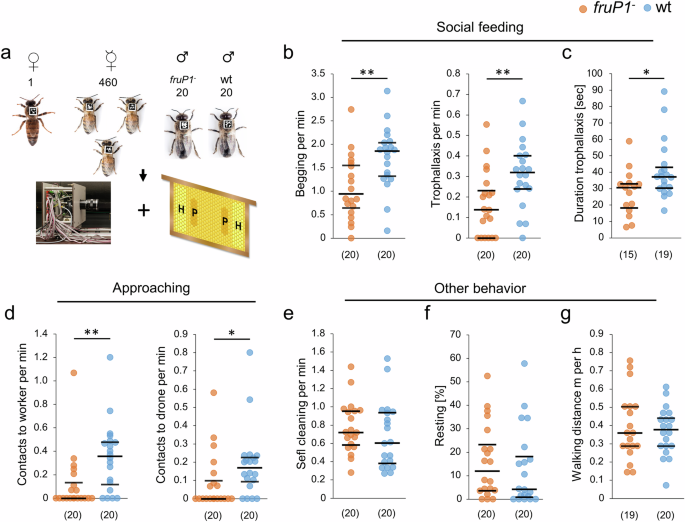

To determine whether the male-specific FruM transcription factor protein hardwires neural circuits that control the social feeding behaviors, we studied loss-of-function fruP1− males in small experimental colonies. Twenty fruP1− males and wt males, together with 460 worker bees and a queen, were assembled on combs (Fig. 5a). These combs contained the same amount of pollen and honey stored at the same location in the cells (Supplementary Fig. S7). The behavior of each male was tracked using unique two-dimensional barcode labels and our computer-based Bee Behavioral Annotation System (BBAS)49 (Fig. 5a).

a Behavioral examination of single fruP1− and wt males in small honeybee colonies using two-dimensional barcoding and computer-based tracking. b Rates of begging (P = 0.004, z = 2.8, MWU test) and trophallaxis (P = 0.005, z = 2.7, MWU test) behaviors. c Duration of trophallaxis behavior (P = 0.027, z = 2.2, MWU test). d Rates of approaching behavior toward worker bees (P = 0.004, z = 3.2, MWU test) and toward males (P = 0.015, z = 2.4, MWU test). e. Rate of self-cleaning behavior (P = 0.21, z = 1.2, MWU test). f Proportion of time spent resting (P = 0.3, z = 1.0, MWU test). g Locomotor behavior (P = 0.94, z = 0.9, MWU test). fruP1− and wt males were compared in two colony replicates. Medians (middle line) with quartiles Q1 and Q3 are shown. (n) below graph (b) to (g): the number of males examined. min minutes, sec seconds, m meters, h hours. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01. All statistical tests were two-sided.

We observed that the rate of begging behavior was markedly and significantly reduced by approximately twofold in fruP1− males compared with wt males (P = 0.004, MWU test; Fig. 5b). Moreover, the rate of trophallaxis behavior was reduced by more than twofold on average in fruP1− versus wt males (P = 0.005, MWU test; Fig. 5b). We found that the duration of trophallaxis behavior was slightly but significantly reduced in fruP1− compared with wt males (P = 0.027, MWU test; Fig. 5c). However, the movement patterns during the execution of begging and trophallaxis behaviors were stereotypic and unaffected, suggesting that the initiation of begging and trophallaxis and the sustainment of trophallaxis behaviors were specifically impaired in fruP1− males (Supplementary Movies 14–17).

Begging behavior requires that a male approach another colony member. To understand whether the male’s approaching behavior is actively controlled and innately specified via the FruM protein or whether it arises passively from random locomotion-driven encounters, we examined the rate at which males approached with their antennae the abdomens and thoraxes of worker bees or males, a behavior that does not lead to begging behavior. We observed that these other social contacts were also substantially reduced irrespective of whether the approached bee was a worker (P = 0.004, MWU test) or a male (P = 0.015, MWU test; Fig. 5d; Supplementary Movies 18–21). This result suggests that approaching behavior is impaired in fruP1− males and is innately specified. The rates of other male behaviors, such as self-cleaning behavior (P = 0.21, MWU test; Fig. 5e), resting behavior (P = 0.3, MWU test; Fig. 5f), and locomotion behavior (P = 0.94, MWU test; Fig. 5g), were not affected in fruP1− versus wt males, suggesting that social feeding behaviors were particularly impaired (Supplementary Movies 22–25). Collectively, these results suggest that the initiation of approaching, begging and trophallaxis behaviors and the sustainment of trophallaxis were specifically impaired in the fruP1− males.

Other male-specific within-colony behaviors are also impaired

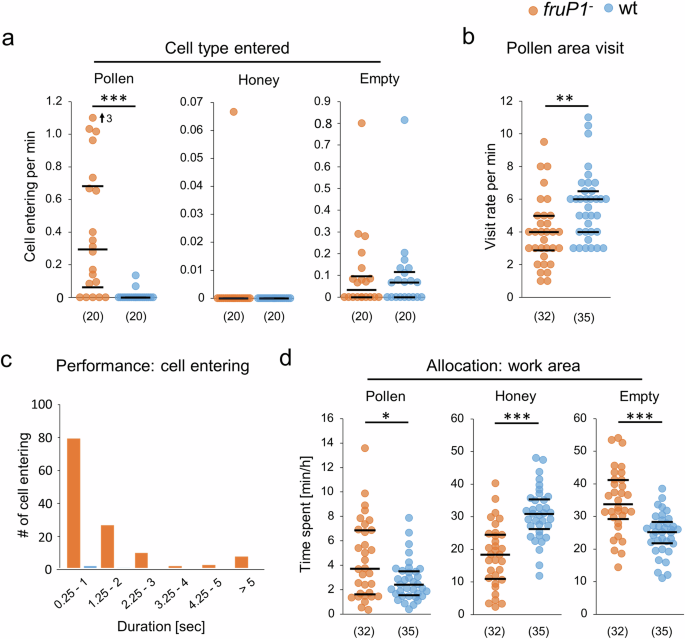

Surprisingly, we observed that fruP1− males repeatedly entered the pollen-containing cells (average 17 times per hour), whereas wt males never did so (P < 0.001, MWU test; Fig. 6a). The fruP1− and wt males did not enter the honey cells (no difference: P = 0.79, MWU test; Fig. 6a), a behavior which has been reported for older males50. Our fruP1− and wt males sporadically entered the empty cells, but the rates did not differ (P > 0.96, MWU test; Fig. 6a). The movements of fruP1− males into pollen cells followed the same stereotypic pattern as those of wt males that entered an empty cell (which often involved bouts of repeated cell entries (Supplementary Table S4 and Supplementary Movies 26–29)). These results suggest that the choice of which cell type is entered is disrupted in fruP1− males. The increase in the entering of pollen cells cannot be explained by higher visiting rates to the pollen stores because the pollen area visits were lower in fruP1− than in wt males (P = 0.002, MWU test; Fig. 6b). Because the entering of pollen cells in fruP1− males lasted for more than 2 s (Fig. 6c), we investigated whether the fruP1− males consumed pollen, a food source they can hardly digest10,12. No sizeable amount of pollen grains was found in the midguts and hindguts of fruP1− males (Supplementary Fig. S8), suggesting that the entering of pollen cells do not result in a consumption of pollen.

a Rates of entering different types of cells on the comb: pollen cells (P = 1.7 × 10−5, z = 4.3, MWU test), honey cells (P = 0.79, z = 0.26, MWU test), and empty cells (P = 0.94, z = 0.07, MWU test). b Rate of visiting pollen areas (P = 4.2 × 10−6, z = 4.6, MWU test). c Duration of entering the pollen cells of the mutant males. d Time spent in the different work areas of the comb: pollen store (P = 0.045, z = 2, MWU test), honey store (P = 1.6 × 10−6, z = 4.8, MWU test), and empty area (P = 4.1 × 10−5, z = 4.1, MWU test). Medians (middle line) and quartiles are shown. (n) below graphs (a, b, d): the number of males examined. sec seconds, min minutes, h hours. In a, an outlier is marked with an arrow, and the value is provided. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001. All statistical tests were two-sided.

Males do not perform any behavioral task inside the colony. They also do not compete with other males over food sources or females8. Hence, males are usually located on the periphery and in the honey areas rather than in the densely populated center of the colony, in which the brood areas and pollen stores are found51. We examined whether the location of the males relative to the food stores is also innately programmed via FruM. We found that the fruP1− spent more time in the pollen and empty areas but less time in the honey area than wt males (Fig. 6d), suggesting that the allocation behaviors towards food stores were impaired in fruP1− mutants. Together, these findings suggest that the allocation towards the food stores and the choice of which food is visited in the cells are innately programmed and involve FruM.

Sex pheromone-related behaviors, but not general sensorimotor functions are impaired in fruP1

− males

Males mate with queens outside the colony during a mating flight. Virgin queens release a sex pheromone (9-oxo-(E)-2-decenoic acid (9-ODA)), which attracts males during these flights52,53. To understand whether the FruM protein also contributes to sexual behavior in the nervous system, we examined changes in locomotion behavior in response to the sex pheromone 9-ODA54 in a behavioral Petri dish assay. Compared with wt males, fruP1− males exhibited reduced locomotion in response to 9-ODA (P = 0.011, MWU test; Fig. 7a), indicating that sexual behavior is also impaired in fruP1− males.

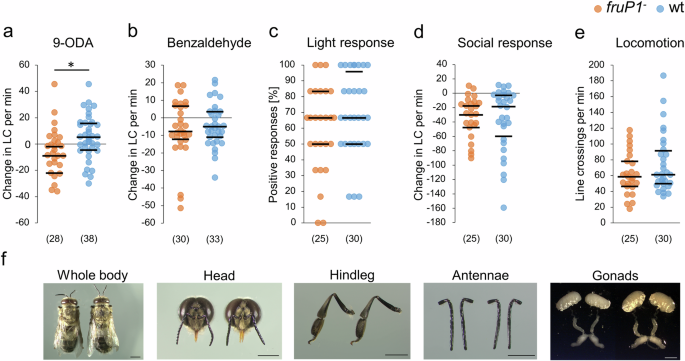

a Locomotor changes (line crossing of a grid in an arena) in fruP1− and wt males in response to the sex pheromone 9-ODA (P = 0.01, z = 2.5, MWU test). The males were at least 8 days old. b Changes in the locomotion of fruP1− and wt males in response to benzaldehyde (P = 0.84, z = 0.2, MWU test). Both fruP1− males and wt males responded to benzaldehyde (P < 0.05, z > 1.9, Wilcoxon rank sum test against zero). c Locomotion response to light stimuli (P = 0.75, z = 0.3, MWU test). d Locomotion changes in response to social contact with two worker bees (P = 0.66, z = 0.4, MWU test). Both fruP1− and wt males responded to these social interactions (P < 0.001, z > 3.9, Wilcoxon rank sum test against zero). e Locomotion without stimulus. P = 0.3, z = 1.0, MWU test). f Morphology and anatomy of wt (left) and fruP1− (right) males. At least n = 7 bees were examined. Scale: 2 mm. Medians (middle line) and quartiles are shown. (n) below graphs (a–e): the number of males examined. min: minutes. *P < 0.05. All statistical tests were two-sided.

To exclude the possibility that the dysfunction of sexual and within-colony behaviors in fruP1− males results from a general impairment of sensorimotor functions (such as a general dysfunction of neuronal processing or moving abilities), we quantified behavioral responses to olfactory, gustatory, mechanical, or visual stimuli. We found that the locomotion responses to the repellent benzaldehyde (P = 0.84, MWU test; Fig. 7b), light (P = 0.75, MWU test; Fig. 7c), and contact with worker bees (P = 0.66, MWU test; Fig. 7d) did not differ between fruP1− and wt males. The locomotion behaviors of fruP1− and wt males in the absence of these stimuli also did not differ (P = 0.3, MWU test; Fig. 7e). Both groups also responded with proboscis extension to honey (P = 0.51, Fisher’s exact test; Supplementary Table 5). Moreover, impaired viability cannot explain the dysfunction of male-specific behaviors because the fruP1− mutation did not influence the survival rate of adult males (log-rank test, Chi2 = 0.22, df = 1, P = 0.64; Supplementary Fig. 9). The behavioral dysfunctions also cannot be explained by a malfunction and malformation of external and internal structures at the gross level because the external head, antennae, abdomen and leg morphology as well as the reproductive organ anatomy of fruP1− males had a wt phenotype (Fig. 7f). These results suggest that general sensorimotor functions are intact in fruP1− males. Hence, the impairment of general sensorimotor functions cannot explain the dysfunction of male-specific behaviors in the mutants.

Cuticular hydrocarbons (CHCs) can provide important cues for social interactions among colony members55,56,57. To examine whether fruP1− mutation altered CHC profiles, we examined the CHC profiles via gas chromatography‒mass spectrometry (GC‒MS) analysis. We observed that all the compounds were present in fruP1− and wt males and that all the compound classes were equally represented (Supplementary Fig. 10). However, there was a significant difference in the overall CHC composition between the mutant and wt males (Supplementary Fig. 10). Next, we examined whether the individual CHC composition profiles of fruP1− and wt males produced separate clusters in two-dimensional multidimensional scaling (MDS) space (Supplementary Fig. 11). We found that the individual profiles partially overlapped between the groups, suggesting that the CHC are unlikely to have triggered a behavioral difference between the groups of mutant and wt bees.

The gross neuropil structure and odor processing features of the AL are not impaired in fruP1

− males

How can the FruM protein specify these male behaviors? We propose that the FruM protein specifies connectivity or functional features in the nervous system that determine behavioral control. To understand the role of the FruM protein in the programming of behaviors, we examined chemosensory receptor abundance, neuropil anatomy, and odor processing in fruP1− males.

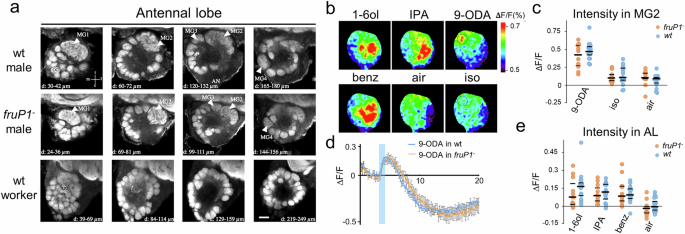

We found no changes in the expression of odorant receptor (OR), odorant binding protein (OBP), gustatory receptor (GR), or chemosensory protein (CSP) genes in the antennae of fruP1− versus wt males using the RNAseq method (Supplementary Fig. 12; EMBL-EBI accession number: PRJEB100586). This result suggests that the repertoire of chemosensory proteins involved in odor detection is not impaired in fruP1− males. This includes the Or11 gene, which expresses a key odorant receptor protein involved in the detection of the queen pheromone 9-ODA15, a gene that is highly male-specifically expressed (>25-fold higher expression in males than in worker bees). Our optical sections of anti-synapsin-labeled midbrains revealed no gross anatomical differences in the neuropil structure or neuron bundles between fruP1− and wt males (Supplementary Movies 30 and 31). Higher-resolution analysis of the AL, the first-order olfactory center, was performed. Four male-specific enlarged and structured glomeruli (MGs) were found in fruP1− males that were in the same location as those in wt males (Fig. 8a)14,18,58. These results suggest that the gross brain anatomy and the sex-dimorphic structure of the AL were not malformed in fruP1− males during development. Finally, we examined whether neural processing features were impaired in adulthood using in vivo Ca2+ imaging of the AL. Odor information detected by OSNs in the antenna is translated into a glomerulus-specific pattern of neural activity in the AL18,47. For the queen pheromone 9-ODA, the activity in fruP1− males was confined to MG2, as in wt males (Fig. 8b). The response intensity did not differ between fruP1− and wt males (P = 0.46, 2-way repeated-measures ANOVA; 9-ODA fruP1− vs. 9-ODA wt males: P = 0.36, Sidak multiple comparison test; Fig. 8c, d). The responses in MG2 were specific to the 9-ODA application in both cases (P < 0.0001, Tukey post hoc tests, 9-ODA vs. control, P < 0.0001; Fig. 8c, d). These observations suggest that 9-ODA odor information processing was not impaired in fruP1− males in this first-order processing center. For other odorants, such as 1-hexanol (1-6ol), the repellent benzaldehyde, and the alarm pheromone component isopentyl acetate (IPA), we also detected no signal intensity or pattern differences between fruP1− and wt males (P = 0.49, 2-way repeated-measures ANOVA; Fig. 8b, e), suggesting no dysfunction in fruP1− males. Collectively, these results suggest that neither a dysregulated neuropil connectivity structure and chemoreceptor protein repertoire nor dysfunctional primary olfactory processing can explain, at this gross level, impaired behavior in fruP1− males.

a Morphology of anti-synapsin-stained ALs. μm indicates the depths represented in the images. n = 9 fruP1− and n = 10 wt males were examined. Arrowheads: macroglomeruli. Scale:50 μm (b). Calcium signals in the antennal lobes of fruP1− males evoked by 4 odorants (9-ODA, 1-hexanol (1-6ol), IPA and benzaldehyde). Different odorants induce different glomerular activity patterns. Relative fluorescence changes (∆F/F [%]) are presented in a false-color code. Dark blue: minimal response. Red: maximal response. Dashed circle: macroglomerulus MG2. c Amplitude of calcium responses (∆F/F [%]) in MG2 to sex pheromone 9-ODA and to air and solvent controls (iso: isopropanol). Medians (middle line) and quartiles are shown. No difference was detected between the fruP1− (red) and wt (blue) groups (genotype effect: P = 0.46, F1,24 = 0.57, 2-way repeated-measures ANOVA. 9-ODA fruP1− vs. 9-ODA wt males: P = 0.36, Sidak’s multiple comparison test). In both cases, responses to 9-ODA were significantly greater than those to the controls (odor effect: P < 0.0001, F2,48 = 65.25, 2-way repeated-measures ANOVA. 9-ODA vs. iso control: P < 0.0001, Tukey post hoc tests. fruP1− (red): n = 10. wt (blue): n = 16). d Average time courses (in seconds, x-axis) of odor-evoked responses (∆F/F [%]) to 9-ODA recorded in MG2. fruP1−: n = 10. wt males: n = 16. Blue bar: odor presentation. Calcium signals show a biphasic response, with increased fluorescence upon odor presentation. Mean values alongside with the Standard Error of the Mean (SEM) is presented. e Amplitude of calcium responses (∆F/F [%]) to 3 odorants (1-6ol, IPA, and benzaldehyde) in the entire AL. Medians (middle line) and quartiles are shown. No differences in response were found between fruP1− and wt males (genotype effect: P = 0.49, F1,25 = 0.48, 2-way repeated-measures ANOVA. Air: air control). Compared with the air control, all the odorants induced significant activity (odor effect: P < 0.0001, Tukey post hoc tests). fruP1− (red): n = 11. wt (blue): n = 16). All statistical tests were two-sided.