Breaking Update: Here’s a clear explanation of the latest developments related to Breaking News:Researchers Use South Pole Telescope to Detect Energetic Stellar Flares Near the Center of the Milky Way | NCSA | National Center for Supercomputing Applications | Office of the Vice Chancellor of Research and Innovation– What Just Happened and why it matters right now.

The universe is vast, but astronomers don’t have to look too far to find something genuinely new. Researchers at the Center for AstroPhysical Surveys (CAPS) used the South Pole Telescope to probe one of the most complex regions of the sky, the crowded inner Milky Way, and uncovered powerful, short-lived bursts of millimeter-wavelength light from two known accreting white dwarf systems. In a region where overlapping sources, dust, and confusion can make discovery difficult, these flashes stood out clearly and point to a class of energetic events that millimeter surveys are uniquely positioned to reveal.

The events, reported in a recent paper in The Astrophysical Journal, represent the first time such flares have been discovered in a wide-field, time-domain millimeter survey. That distinction matters: rather than targeting a pre-selected list of candidate objects, the survey repeatedly scanned a large swath of the Galactic Plane and caught the flares serendipitously. The result demonstrates that high-cadence millimeter mapping can do more than measure static emission. They can also detect fast, rare transients and open a new observational window on the dynamic astrophysics of the Milky Way’s central environments.

“We’re just starting to understand what’s possible,” said Yujie Wan, lead author of the study and graduate student in the Department of Astronomy at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. “There is so much happening at the center of our galaxy that we’ve never been able to observe at these wavelengths. This discovery is the first step toward a much richer picture of the Milky Way.”

The detections came from the SPT-3G Galactic Plane Survey, the first dedicated high-sensitivity, wide-field, time-domain, millimeter survey of the Galactic Plane. Using the 10-meter South Pole Telescope, the team repeatedly observed a roughly 100-square-degree region toward the Galactic Center in three millimeter bands. Over multiple seasons, the survey accumulated hundreds of repeated observations of the same patch of sky—enough to notice day-scale variability and to distinguish genuine astrophysical flares from noise, weather, or instrumental effects. Analysis of the first two years of data alone revealed two distinct transient events, highlighting both the rarity of the phenomenon and the power of persistent, systematic monitoring.

Unlike previous SPT surveys that focus on cleaner, high-latitude fields optimized for cosmology, the Galactic Plane Survey intentionally targets a different and much denser volume of the Milky Way. By looking toward the inner galaxy, the survey probes regions with far higher source density and richer astrophysical complexity, where compact objects, star formation and extreme environments are more common. That strategy improves the odds of catching bright events at larger distances, but it also raises the bar for data processing and validation. The field is crowded, the backgrounds vary and distinguishing a transient point source from complex extended emission requires careful analysis.

Researchers at CAPS, based at the National Center for Supercomputing Applications (NCSA), collaborated with an international team to develop the analysis necessary to identify transients: sudden, short-lived bursts of emission that appear and fade on timescales of hours to days. In this case, each flare lasted roughly one day. While that might sound long compared to milliseconds-long radio bursts, it’s brief in the context of most astronomical variability and places strong constraints on the size and physical mechanism of the emitting region. Importantly, the events were detected in millimeter bands where transient discovery has historically been far less common than in optical or X-ray surveys.

“Historically, most astrophysical transients are detected at optical or X-ray wavelengths,” said Joaquin Vieira, astronomy professor and director of CAPS. “Finding them in the millimeter band gives us a new way to study how these systems behave, especially in a region as complex and crowded as the Galactic Plane.”

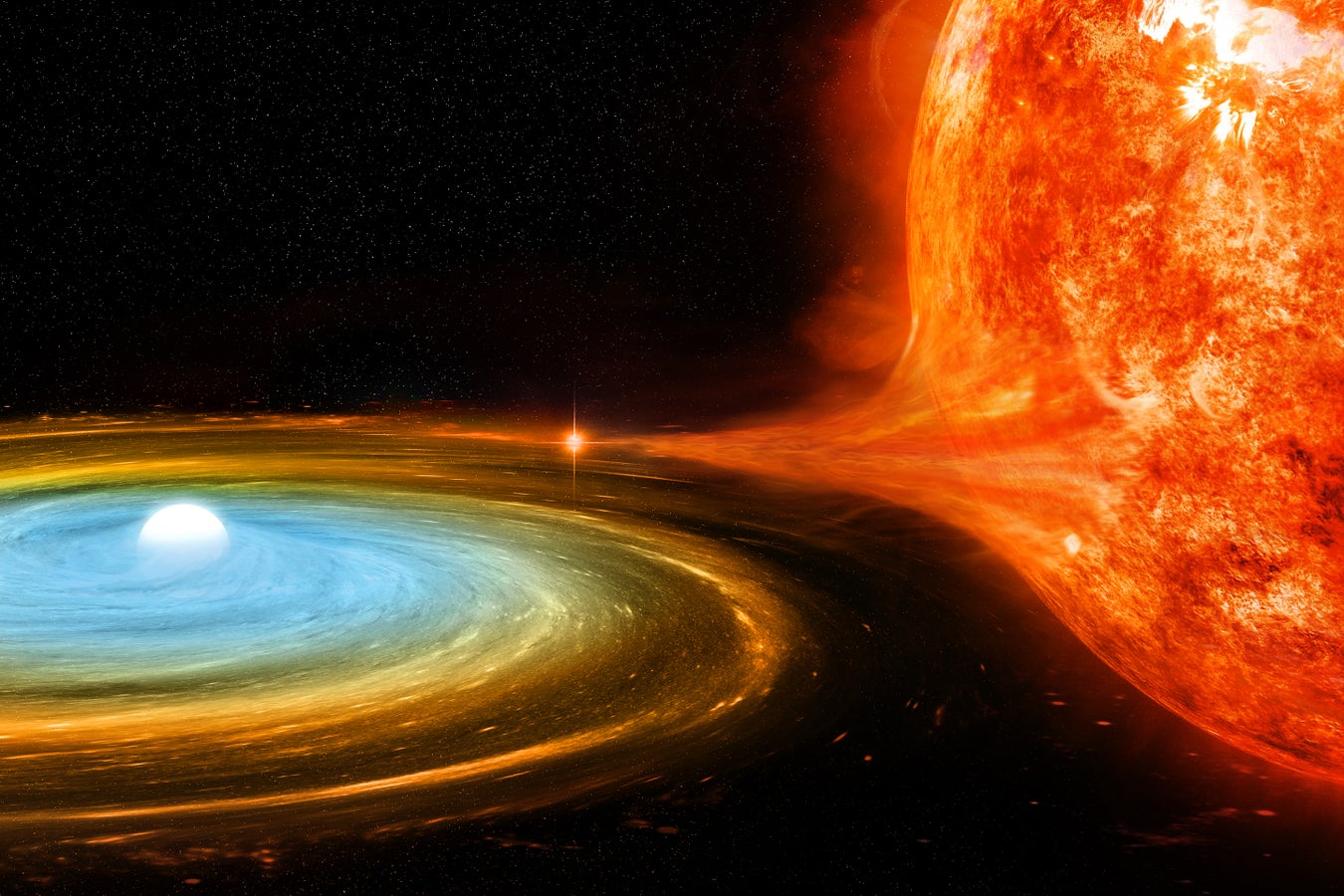

The sources of the outbursts are accreting white dwarfs locked in close binary orbits with companion stars. As the white dwarf’s gravity pulls gas off its companion, the material forms a swirling accretion disk that heats up and can drive powerful variability across the electromagnetic spectrum. These systems have been studied for decades, but the millimeter regime has not traditionally been the primary place to discover their most dramatic behavior, which makes this detection both surprising and scientifically valuable. It suggests that millimeter emission can be an important tracer of rapid energy release in accreting binaries, potentially tied to shocks, magnetic reconnection, or particle acceleration in the disk environment.

The team suspects the flares were triggered by sudden magnetic explosions in the accretion flow—an analogue to solar flares, but operating in a far more extreme setting. In the sun, magnetic reconnection can rapidly convert stored magnetic energy into heat and energetic particles. In an accretion disk around a compact object, similar processes can occur at much higher densities and energies, potentially producing bright, short-lived bursts that propagate outward and radiate across multiple bands. If this interpretation holds, millimeter observations may offer new insight into the magnetic physics of accretion disks, which is central to understanding how compact binaries evolve, how they transport angular momentum, and how they generate outflows.

Beyond the excitement of two events, the broader implication is statistical: if a wide-field survey caught two rare, luminous flares in its first analyzed years, then continued monitoring should reveal more, and perhaps uncover entirely new types of millimeter transients. A larger sample will let the collaboration measure how common these flares really are, whether they occur preferentially in certain types of binaries, how their brightness and duration are distributed, and whether they correlate with activity seen in optical, X-ray, or radio follow-up. The team plans to dig deeper into the data to improve sensitivity, examine both longer and shorter time scales for different types of transients, and automate the transient detection algorithm to automatically send out alerts to the community.

“The South Pole Telescope continues to enhance the nation’s world-leading science program in the polar regions and to fulfill the promise of Antarctica as a premier site for astrophysical observations,” said Marion Dierickx, the U.S. National Science Foundation (NSF) program director for the South Pole Telescope. “This first-of-its-kind detection opens new pathways for advancing our understanding of the universe.”

The SPT-3G Galactic Plane Survey will continue observing the Milky Way for about a month each year, building a longer and more sensitive time-domain record of the Galactic Center region. With each new season, the survey strengthens the case that millimeter astronomy is not just about mapping the static universe—it can also capture the Milky Way in motion, revealing brief, energetic flashes that reshape our understanding of compact binaries and the dynamic inner galaxy.

“We’ve only searched for transients in two years and already found two remarkable events,” said Tom Maccarone, a physics professor at Texas Tech University and collaborator on the project. “This is a great example of the adage among astronomers that opening new windows on the universe produces new, unexpected, exciting results. We’ve only scratched the surface of what can be done with millimeter transient surveys of the Galactic Plane and are looking forward to discoveries of many more new events in years to come.”

CAPS, a research unit hosted at NCSA, provided expertise in data analysis of the survey. CAPS, the Department of Astronomy and the Department of Physics at the University of Illinois are among the 38 different entities across the world that contributed to this new research. The South Pole Telescope is primarily funded by the NSF and the Department of Energy and is operated by a collaboration led by the University of Chicago. NSF supports the South Pole Telescope program through awards OPP-1852617 and OPP-2332483.

For more information, contact Professor Joaquin Vieira: jvieira@illinois.edu.