Breaking Update: Here’s a clear explanation of the latest developments related to Breaking News:Scientists Develop a New Way To See Inside the Human Body Using 3D Color Imaging– What Just Happened and why it matters right now.

A newly developed imaging method blends ultrasound and photoacoustics to capture both tissue structure and blood-vessel function in 3D.

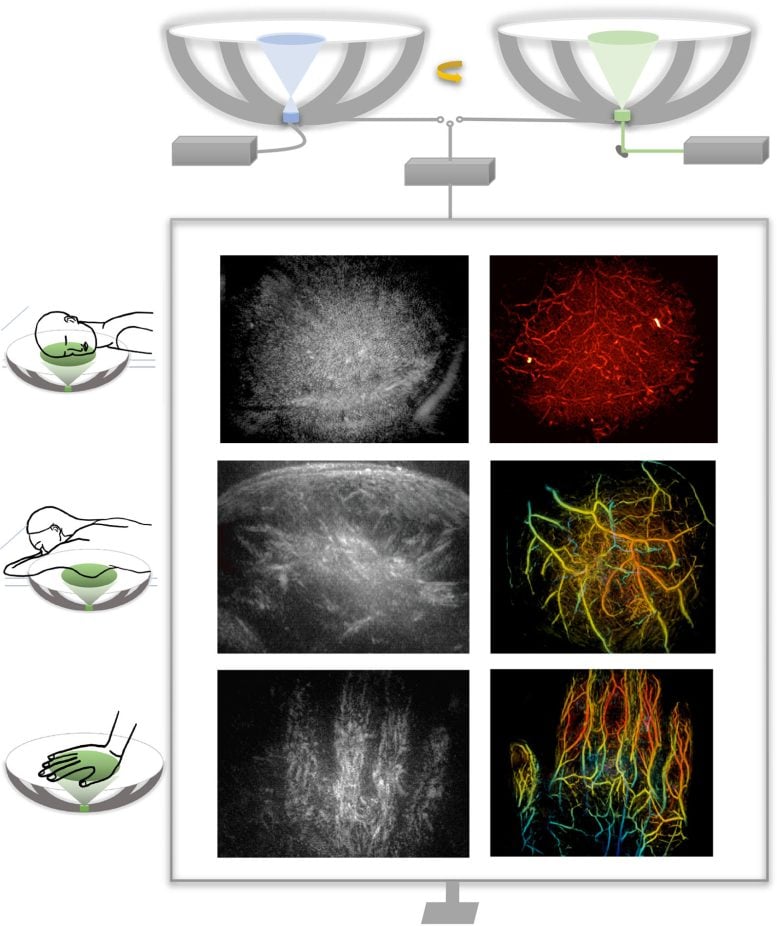

By blending two powerful imaging methods, researchers from Caltech and USC have developed a new way to see inside the human body with unprecedented speed and detail. The technique produces three-dimensional, full-color images that show not only the shape of soft tissues but also how blood vessels are functioning in real time. In early demonstrations, the researchers successfully imaged several different parts of the human body, highlighting the versatility of the approach.

This combined imaging method could significantly improve how doctors detect and study disease. Potential applications include more precise breast tumor imaging, new ways to track nerve damage caused by diabetes, and advanced tools for observing brain structure alongside blood flow. The work suggests a path toward medical scans that are both more informative and easier to repeat over time.

The researchers describe the new technology in a paper published in Nature Biomedical Engineering.

Medical imaging often requires tradeoffs between speed, cost, and the type of information that can be captured. Ultrasound, one of the most widely used techniques, is fast, inexpensive, and well suited for visualizing the structure of tissues. However, it typically provides only two-dimensional views and cannot easily capture a wide area or reveal detailed information about blood chemistry or flow.

Photoacoustic imaging addresses some of those gaps but introduces others. In this approach, laser light is sent into the body, where it is absorbed by molecules in blood vessels. That absorption generates sound waves that can be detected and translated into images. Because different molecules absorb light in distinct ways, photoacoustic imaging can display blood vessels in optical color—allowing for visualization of how blood moves through arteries and veins. On its own, however, the technique does not provide enough structural detail to fully map surrounding tissues.

Other advanced imaging tools, such as computed tomography (CT) scanning and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), can deliver detailed views of anatomy, but they come with notable downsides. These methods can be costly, may require contrast agents, sometimes involve exposure to ionizing radiation, or take too long to be practical for frequent monitoring or bedside use.

Combining Ultrasound and Photoacoustics

To overcome these limitations, the researchers developed RUS-PAT (rotational ultrasound tomography, RUST, combined with photoacoustic tomography, PAT). PAT was first developed more than two decades ago by Lihong Wang, the Bren Professor of Medical Engineering and Electrical Engineering and the Andrew and Peggy Cherng Medical Engineering Leadership Chair at Caltech.

In PAT, molecules that absorb light respond to short laser pulses by vibrating, which generates acoustic signals. These signals can then be detected and processed to form detailed, high-resolution images.

Wang, who is also the executive officer for medical engineering at Caltech, says his group’s aim with the current work was to combine the benefits of PAT with ultrasound. “But it’s not like one plus one,” he says. “We needed to find an optimal way of combining the two technologies.”

Ultrasound typically uses many transducers to both generate and receive ultrasound waves, and combining this process directly with PAT would be too complex and expensive for widespread use. PAT, meanwhile, only requires the detection of ultrasound, and that gave Wang an idea. “I thought, ‘Wait, can we just mimic light excitation of ultrasound waves in photoacoustic tomography, but do it ultrasonically?’” PAT allows laser light to diffuse within the tissue, ultimately triggering the production of measurable ultrasound waves. Similarly, Wang figured, they could use a single wide-field ultrasound transducer to broadcast an ultrasonic wave broadly into the tissue.

They could then use the same detectors to measure the resulting waves for both modalities. In the new system, a small number of arc-shaped detectors are rotated around a central point, allowing it to behave like a full hemispheric detector but at a fraction of the complexity and cost.

Demonstrated Clinical Potential

“The novel combination of acoustic and photoacoustic techniques addresses many of the key limitations of widely used medical-imaging techniques in current clinical practice, and, importantly, the feasibility for human application has been demonstrated here in multiple contexts,” says Dr. Charles Y. Liu, an author of the paper who is a visiting associate in biology and biological engineering at Caltech. Liu is also a professor at the Keck School of Medicine of USC, director of USC’s Neurorestoration Center, and chair of neurosurgery at the Rancho Los Amigos National Rehabilitation Center.

The RUS-PAT technique could potentially be used in any region of the body to which light can be delivered, and for applications where clinicians or researchers would benefit from the synergistic imaging of both the morphology and color-related function. For example, RUS-PAT could improve breast-tumor imaging, giving physicians the ability to know a tumor’s exact location and surroundings as well as its pathology and physiology. It could also help doctors monitor the nerve damage caused by diabetic neuropathy by providing an all-in-one way to monitor oxygen supply along with morphology. Wang says the technique could also be useful in brain imaging, allowing scientists to observe the structural details of the brain while also being able to observe hemodynamics.

Currently, the system can scan to a depth of about 4 centimeters. Light can also be delivered endoscopically, potentially making deeper tissues accessible to the new technology. A RUS-PAT scan can be performed in less than one minute.

The current setup involves a scanning system with ultrasound transducers and laser housed underneath a bed. It has been demonstrated on human volunteers and patients and is in the early stages of translational development.

Reference: “Rotational ultrasound and photoacoustic tomography of the human body” by Yang Zhang, Shuai Na, Jonathan J. Russin, Karteekeya Sastry, Li Lin, Junfu Zheng, Yilin Luo, Xin Tong, Yujin An, Peng Hu, Konstantin Maslov, Tze-Woei Tan, Charles Y. Liu and Lihong V. Wang, 16 January 2026, Nature Biomedical Engineering.

DOI: 10.1038/s41551-025-01603-5

The work was supported by funding from the National Institutes of Health.

Never miss a breakthrough: Join the SciTechDaily newsletter.

Follow us on Google and Google News.